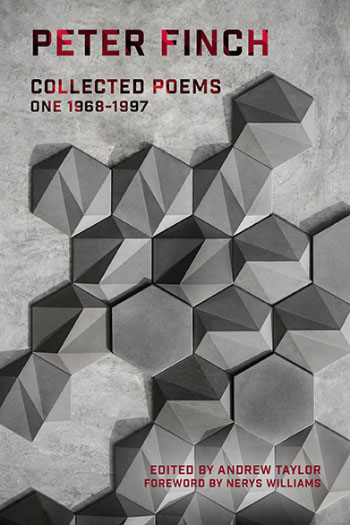

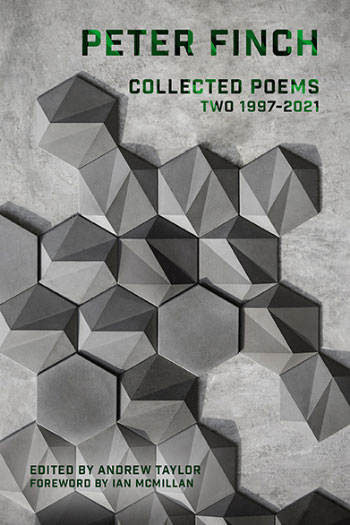

Peter Finch Collected Poems is published in two volumes running to almost a thousand pages. The books are edited by Andrew Taylor with forewords from Ian McMillan and Nerys Williams. From the 60s to the 2020s Finch's poetry has been gathered. His visual work has been repaired, his innovations strengthened, his verse represented in all its wide variety.

These books chart the course of a remarkable writing career. From his start among the small presses, his engagement with the UK poetry reading scene, his involvement with the avant garde, his participation in the poetries of everywhere from Wales to Waikiki and his determination to make all this as public an activity as he could. He founded Second Aeon magazine and publishing house, started a poetry and music band, ran small press bookfairs, bookshops, bookfairs, writers associations, the Welsh Academy and, before he retired, became the Chief Executive of the agency Literature Wales. He was a poetry entrepreneur in all senses of the word. He brought to all these things an unquenchable vitality which set him apart in contemporary poetry.

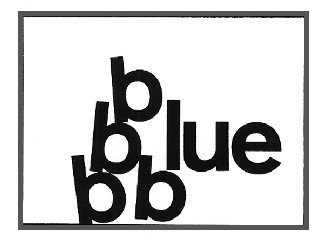

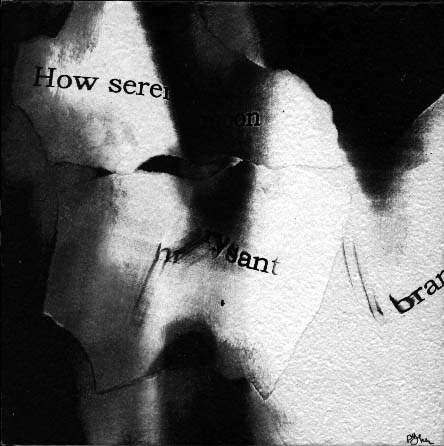

The first volume makes available poems from lost chapbooks, broadsheets and limited editions, as well as more conventionally published work. Here are concrete poems, sound poems, typographical poems, visual poems, poems in cartoon form or as crumpled photocopies. Whatever their structure, Finch's poems are always vivid and alive, pulsing with inventive energy. As he says himself, this is work which pushes the idea on until it breaks, flowers, or dissolves. Finch's writing can never be taken for granted.The second volume includes poems from further on into his career, in which poetry also began to appear in his prose books, and in the public realm on sculptures, walls and buildings of his native Cardiff. This work continued to 'operate at the far edges of what poetry is understood to be'. Although the poetry landscape of Britain might have changed since his first published poem in 1965, his desire to experiment, to question what constitutes a poem, and to challenge orthodoxy has remained both undiminished and relevant.

The Collected Poems demonstrates also a restless exploration of the ideas behind the work itself. It is a testament to the experimental in literature, to ways of pushing boundaries and of doing things differently, and to an alternative modernist culture in Wales and Britain.Consequently, and invaluably, Finch's work opens a window on a poetry scene seemingly lost from view to the twenty-first century. It reminds us that there was interesting and vital writing happening outside of what has now calcified into the canon of twentieth century British poetry. And that Finch was at its cutting edge.

Editor Andrew Taylor has included an informative Introduction, an extensive timeline of Finch's artistic activity, along with helpful notes. Vol One has a preface by poet Nerys Williams. Vol Two has a preface from Ian McMillan.

Copies directly from Seren

Signed copies available with a special two vols almost for the price of one offer. Don't miss it.

What the Critics Say

Mab Jones in Buzz

There's a word, 'Finchian', meaning "like the writing of Peter Finch". Whether you're familiar with Finch's writing or not - as one of the UK's leading poets, you need to be! - it might be useful here to think of finches the birds: sharp-eyed, smart, and agile; sometimes musical, often colourful; as a family, remarkably diverse - all descriptions that could be attributed to the work of Finch himself.

I first heard the poet on the radio when I was a teenager; now, as an adult, I was pleased to be present at the launch of the poet's collected poems, which marks the culmination of nearly 60 years of publication. This two-tome volume is weighty, stylish, and chock full of poetic delights, from proclamation and provocation to concrete and cut-up, including list poems, prose poems, pictorial poems, and more. Poems might contain an excess of brackets, or numbers, or be made up of words that slide and smear across the page. They may resemble a telephone directory; form a circle or the shape of a planet; or be entirely diagrammatic. Poems might also be 'poem-shaped', resembling what we think of as poems, but Finch might well use that form to subvert and surprise, too.

Unpredictable and exciting, these books show the sheer range of the poet, and why he does deserve his own descriptive word. One of the first poems in the collection, A Welsh Wordscape, summarises exactly what Finch isn't:

"To live in Wales,

Is to be mumbled at

by re-incarnations of Dylan Thomas

in numerous diverse disguises"

Well, Finch isn't an imitator, but he does still carry through that flaming torch of pure unbridled energy which we associate with Thomas. Personally, I find Finch far less morose than Thomas, who could at times sermonise; there is no such leadenness here. Finch has always been and still is, experimental, with a daring and intelligent imagination that is enviable. He's always been a poet who lifts up, and off, into airy new terrain… Finch-like. Finchian. A must-read collection, of course.

- Mab Jones in Buzz. "New poetry for June: Welsh summer special."

Rupert Loydell in Tears In The Fence

The small press world was very different in 1982 when my friend Graham Palmer and I started Stride magazine. Magazines were analogue, usually photocopied or duplicated, often stapled by hand, and sales were via mail order unless you could persuade ‘alternative’ bookshops to take copies on sale or return. Even when booksellers were friendly and did sell copies, it was hard to extract money from them; and sales never covered the petrol I used up motorcycling round London stores or driving the meandering route I sometimes took to drop copies off in Oxford, Leamington Spa, Coventry, Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester…

There was, of course, no internet, email, or social media. You could swop flyers, leave them in bookshops or the South Bank poetry library, and send review copies out – often in exchange for magazines you were expected to review. There were small press fairs, often in draughty halls in strange towns or cities, with little publicity and even fewer sales, though you did get to meet other publishers and poets. I particularly remember the first time I met Allen Fisher and Alan Halsey in Shrewsbury, and also meeting and propping up a bar in Northampton with Mike Shields (of Orbis) and Martin Stannard because the main room with our stalls in was suddenly – and unforgivably – commandeered for an all day poetry reading.There were small press poets who immediately got in touch with every new magazine who editors soon learnt to ignore, along with submissions of rhyming doggerel, but there was also the delight in hearing from new authors, and in becoming part of something that seemed alive and experimental, with a history of 1960s and 70s revolutionary zeal, readings and magazines, but that now walked hand-in-hand with post-punk and improvised music, music zines and independent cassette labels, radical theatre, and new performance and exhibition spaces.

There were of course key individuals within the small press scene, often at odds with the likes of the Poetry Society and ignored by mainstream poetry publishers, and there was one more key than others: Peter Finch, who operated out of Oriel, Cardiff. He had previous with his own small presses, and actually wanted to stock new magazines, wanted to submit to yours (and mine), wanted you to keep going, wanted you to be different, opinionated and make things possible; he would heckle and encourage. He put on poetry festivals and events in Cardiff, which is where I was first introduced to him in person by the writer John Gimblett. I had a Stride stall, did a reading, and watched Bob Cobbing and Bird Yak clear a restaurant with their mix of yowling, abstract drumming and gas-mask one-string guitar. I’d seen plenty of that kind of stuff at the London Musicians Collective, usually with five or six others watching, but nobody except Finch would think of sticking them in front of 200 people eating their lunch and then enjoy watching the diners’ responses and subsequent mass exodus, leaving full plates and wine glasses abandoned on the tables.

Since then I’ve promoted a couple of Finch readings in Exeter – one as a support act to Roger McGough, which he smashed; read once or twice more in Cardiff for him; and co-tutored an Arvon Foundation course with him. And although I’ve failed to tempt him down to Cornwall, we’ve kept in vague touch via emails and poems. I’ve also amassed – courtesy of jumble sales, library turn-outs and secondhand bookshops – quite a collection of early Finch publications, which helped explain the amazing and informed talk he gave at Arvon on Sound and Visual Poetry, and also offered critical context.

Because, as these hefty new books make evident, Finch came out of Dada and Surrealism, out of performance and sound poetry, out of collage and cut-up, erasure and what we now call sampling and remix. His work is entertaining, experimental, thought-provoking and accessible; a real pick’n’mix in fact. But Finch knows what he is doing, and over the years I learnt to trust him completely as an editor and poet. When he opened for Roger McGough in a sold out Exeter theatre he began with an abstract sound poem, and I confess I had a moment of panic. Soon, however, the audience, who were mostly there to see the headliner, began nervously laughing before guffawing and offering wild applause. Finch reeled them in further with a couple of more straightforward poems and kept them in the palm of his hand for the rest of his varied performance.

It’s great that Seren have given Finch (and his editor Andrew Taylor) so much space to fill, and have reproduced so much of Finch’s visual work, some even in colour. Subject matter, processes, affectations, source material and poetic influences, enter, exit and re-enter the work, but there are always new materials, new processes and ideas in the mix too. There is also a sustained attention to and curiosity about language itself: how it can be remoulded, changed, abused, erased; what happens when syntax or meaning is destroyed, when different vocabularies or reference materials collide, when texts are alphabetized, torn up, or turned into lists. How poetry can be made new. Always.

This work sprawls and expands, feeding on itself and everything that is around it. It comments and critiques, dances and debates, screams and shouts, sometimes sulks in the corner but then quietly comes out rested and refreshed, raring to go. It is alert, blurred, crumpled, distressed, energetic, folded, gorgeous, hilarious, incredible, jokey, charismatic. It is often ridiculous, always serious, never afraid to embarrass itself or satirize others, whilst constantly acknowledging Schwitters, Cobbing, Ginsberg, and whoever Finch has been reading that morning. It is questionable, ridiculous, subversive, terrific, unique poetry which cannot be snared, trapped or caged; yet Taylor and Seren Books have charmed it on to the pages of this generous, rain-filled, assertive, definitive collection. I look forward to volume three.

-Rupert Loydell in Tears In The Fence, July 11, 2022

Bob Mee - The Idea of a 'Collected Poems' Has Always Seemed a Scary Prospect ...

… As in – What? You want to dig out everything I’ve ever completed or abandoned and put them all in a book? Why? Some will be so bad they’ll be embarrassing.

Except it’s the type of thing that usually happens to more accomplished and better known writers than me, and usually when they’re dead, so the truth is there is nothing to be frightened of. On the opposite side of the experience, reading every poem someone has written might seem a massive and potentially draining task unless you were planning to write an academic thesis. Even so, I was fascinated by the idea of Peter Finch’s two-volume Collected Poems (Seren, £19.99 each book) given that he had so much of his early work in long out-of-print small magazines – and that he is still alive.

As a kind of preparation, I looked again at Philip Larkin’s Collected Poems, published in 1988, three years after his death. It’s illuminating to see how organised and competent a writer he was when he was still so young, though perhaps that’s in part a result of the constraints of his time, in that it was easier to know then where to pitch oneself if you wanted to write poetry and were English. But what did I gain from reading all of those early poems, including one published in a school magazine when Larkin was sixteen? Sadly, the answer is not a lot.

What would Larkin have thought of it? True, he kept meticulously dated notebooks, to the point where an individual poem could be traced over time, but I am not sure that the legendary librarian of Hull University would have approved of every single one of the contents of these personal books being lumped together and offered to the general public as proof, one way or the other, of his historical standing. Perhaps the limit of his intentions in keeping the notebooks was to offer any future students a chance to assess him in terms of an essay here, a thesis there. (Or maybe he’d wanted them thrown out when he had gone.) But the whole lot thrown together for public consumption?

Finch, being alive, at least has been able to control what’s included and what is quietly omitted. And, even if that makes it a kind of Selected Collected Poems, I don’t blame him a bit. This way, we know he feels there is, or might be, some value and relevance in each of the pieces that are included.

And I do prefer the idea of a Collected Poems, good, bad and indifferent, to one of those slim Selected Poems volumes that only scratch the surface of what a poet is about. I’m thinking of another book on the shelf, the unsatisfactory, 33-poem selection of W H Auden’s work, published in 1968. I believe Auden was involved in the production of that, so must take some responsibility for it. However, so much is left out that it runs like a brief introduction. And, of course, there was so much more to come.

Back to Finch, whose work now stretches back more than fifty years. He, and everyone else involved with the project, will know the collective effort and dedication that is required to get something like this into print. It’s huge but admirable – and, in my view, well-deserved, if the arrival of a Collected Poems is, in the end, to be considered an accolade.

I had a fairly inadequate stab at considering what Finch is about in a previous blog, centred on the books I had bought of his over the years, so don’t intend to attempt an in-depth assessment of the 950-odd pages in the two volumes. Sufficient to say that as usual, while there are orthodox, plainly written pieces, some apparently personal and anecdotal, and therefore easy to understand, in others the boundaries of what people might perceive a poem to be are tested again and again. (If you want to see the earlier blog, it’s under the title of The Value Of Doing Things Your Own Way – A Brief Look At The Work Of Peter Finch, from June 2021.)

Years ago, on a work trip, a colleague picked up a book of Diane Wakorski’s work that I had with me. He read a couple of the poems, looked mystified and said: I don’t understand. Is this poetry or is it just ideas? As usual, I found it hard to respond. I am no defender of anyone’s poetry, including my own, or other kinds of writing for that matter, and for all the time I’ve been writing I still can’t explain exactly what poetry might or might not be. That, perhaps, to me, is the point – and why I find Finch interesting.

My friend put Wakorski’s book down and took the traditional higher ground that poetry wasn’t poetry if it didn’t rhyme. There wasn’t much point in telling him about Paradise Lost or The Prelude but stupidly I did attempt a vague stab at the suggestion that poetry may have used rhyme because travelling, illiterate balladeers found it easier to remember the words if they had the comfort of rhymes to hold on to, rather like most songs. Once it started to be written down and published, by those who could write and afford to publish, this was no longer necessary, although for centuries people preferred it that way and many still do. Yes, folks, I came across as a pretentious idiot, sensed it, and fell back on the weary old chestnut In the end, it’s what you like, which always translates as I’ve no idea what I’m talking about.

What my colleague would have made of Finch, I can’t imagine. We have the concrete poems, sound poems, performance poems, whatever comes into your head poems, even images of, for example, crumpled pieces of paper, purported to be critical reviews in poetry mags of the time.

He does what he wants and does it his own way. We don’t have to like everything he does. He would probably think there was something slightly wrong with us if we did because the point is that he’s trying to challenge us to rethink, reconsider, wonder why something he has done in an apparently odd way is how it is. I enjoy the way he explores ideas, in the methods he uses to communicate as well as in the more formal texts.

In his foreword to the second book (1997-2021), Ian McMillan recalls the time Finch was guest poet at Ty Newydd, the longstanding venue for those who want to attend poetry courses. McMillan, who was teaching there, asked Finch to liven things up a bit – perhaps a daft and dangerous thing to do! Finch responded by reading chunks of a Mills and Boon novel, tore pages out as he read them – and ate them. McMillan felt that in doing so he challenged the relationship between writer and reader, performer and audience.

Terms like avant-garde, concrete, experimental, inventive, alternative are so often applied to poets the world doesn’t quite understand or can’t pigeon-hole. I don’t want to go too near those traps but to interest me a poem has to feel like it’s living, breathing, feeling. At his best, Finch involves me in his work in this way.

Some will inevitably gloss over the stranger pieces because they won’t ‘get’ them. Sounds, images, images which combine with texts, found poems, all fit with a quotation from Finch, included by Andrew Taylor in his introduction, where he says: It is a perfectly respectable approach to make poetry from not what is inside the head but from the swirl of words outside it.

Taylor also calls Finch one of Britain’s leading poets. I’m not really sure what one of those is but I take the point that Finch is trying to challenge where poetry might take us – and in that sense is attempting to lead us somewhere, anywhere, perhaps he’s not exactly sure where, to offer us the potential to move our own writing into places we had not previously considered taking it.

There are just too many pieces in this spread of more than half a century of writing to pick up quotations or select one over another. Enough to say I know I will read and re-read, look at, dip into these two books, as and when, for a long time to come. I am grateful to Finch himself and to Seren for having the energy and ambition to make them available.

-Bob Mee in Poetry And More, July, 2022

Mark Blaney - Things Fall Together | On Peter Finch's Collected Poems

This is almost 1,000 pages of poetry, stretching from 1968 until 2021. You might think, why not add a couple of new poems and it could have 2022 on the cover; and of course the answer is that Finch has another book coming out later this year. The man is unstoppable.A quick recap if you are new to Finch: the poems range from the formally inventive to the conventionally formal. He is well-known in Wales as an innovator, a surrealist, a relentless experimenter. His collections mash up art, the concrete with the mainstream, the list poem, the poem with no words at all and the downright weird. So to nail him down to a philosophy or an aesthetic seems overly ambitious, but there’s a thread running from his first published work in 1968 through to what he’s going to write tomorrow – things fall apart. His drive is a restlessness, an inability to accept the status quo, a free acknowledgement that everything is in flux and that to deny this or try to impose order on the unorderable is doomed to failure. We don’t want things to fall apart, and the struggle against it is what gives Finch the fuel for his vehicle.

The abstract work makes us experience this by his refusal to conform to what we might think a poem is. Consider the first line of ‘Politic’, a poem from Math (1996):

The modern is (could be) always (inevitably) historically (mythologised) possibly (certainly) at war (rebuilding) (restructuring) (unplating) with what comes (arrives) (sails) immediately (historically) before (after) it.

Now, there’s a lot going on in there, but if your first reaction is to find it incomprehensible – don’t worry. Imagine being a surfer. The thrill of surfing is not in trying to control the water; the thrill is in fearing you might fall off.

More conventional poems explore entropy in more explicit ways. In ‘Roofer’, ‘black sludge everywhere’ and ‘the tar fix to repair / the flat roof fails as I watch it.’ In ‘House Painting’, the narrator decorates a wall whilst new neighbours are ‘eating things on sticks’ whilst ‘thinking how hard it is / to change anything for long’:

We’re there. This is the future.

I wet the brush,

try again.

Many of the non-narrative poems are ‘about’ order breaking down and stability turning to decay. Sometimes poems falter until the words and then the letters themselves degrade, ending in a static-like hiss. Putting together the Seren collections has involved some heavy-duty excavation; with many of the original pamphlets in extremely limited editions, a long time ago, much has vanished or has slipped down the side of Finch’s sofa. The appeal of the typewritten poem is its imperfections, and in an endnote for ‘Blues,’ the editor explains that the lost Olivetti typewriter originals are recreated with a font designed to mimic its decayed look.

If most of us are in a battle to impose order on chaos, the corollary for Finch is that we can make a poem out of anything. At the launch a few weeks ago, someone asked Finch his tips for conquering writers’ block. Good question – we’re in expert company here. Stand up. Take a book – ‘this is an old Mills & Boon novel,’ Finch explained, ‘I got it for 5p in a charity shop.’ Rip the book apart – physically destroy it. The pages scatter to the floor. Pick pages up at random. Read out lines that leap out. Stitch them together, and you have a poem. The cut-up technique has had its day, but as a workshop exercise it’s one of many useful things you can learn from watching Finch in action. It’s a jumping-off point for something else, and you won’t know what until you get there. Rather like stretching before exercise, you find you can run further.

At the end of the launch the more gig-inclined of us found scraps of abandoned Mills & Boon as souvenirs. ‘…kissed Viola elegantly, looking proud and yet modest in some indefinable way,’ mine says.

Bubbling beneath all of this is Finch’s second theme – the individual’s place in the wider scheme of things. This is the middle eight, if you like, in his rock song. ‘Out at the edge’ sees the poet on a Pembrokeshire headland, looking towards America: ‘but don’t see it. / Mist, distance, earth’s curvature, / or maybe it just isn’t there.’

In ‘Mountains: Sheep’ he pauses in the middle of nowhere, annoyed by some graffiti. ‘While I seethe / they stand and shit. / When I go / they stay.’ The world carries on regardless, whether we’re there or not. Finch is touching at the existential here; keep grinding away at this idea and, like the typefaces, our sense of identity, purpose, fades and vanishes. But – as always – it’s done with humour. For someone who might be described as a ‘difficult read’, he is not a difficult read. ‘We communicate largely by the act of communicating,’ he informs us in ‘Talk Talk’.

Some poetry folk think you can’t be any good if you’re funny, or at least you’re more likely to be a better poet if you’re not funny. Because being good is serious, isn’t it? At the very least, you can’t be both funny and good in the same poem. Finch would disagree. Intelligence means having perspective and having perspective means you have, or should have, a sense of humour. In fact he wouldn’t even disagree; he’d politely demur that there isn’t a discussion to be had. In ‘Lost’, for example, he finds himself looking ‘in my mother’s shed for a missing cat I’ve never seen.’ The set-up is well-observed melancholy. ‘The rain on my back like 1940 and / my father’s hat still on the door.’ The ending conveys loss and a somewhat Pooter-ish isolation in perfectly-pitched, unresolved humour. ‘A cat skits along the bungalow ridge tiles. / Could be the one. Who knows.’

On Planet Finch, if you see a random gathering of stones, your mind whirs away kinetically in ways that the stones themselves do not. ‘they could build / a wall, a harbour, couldn’t they? / they don’t’. Only rarely does he drift into the sour. The uncharacteristic ‘Meeting her lover’ vents an anger that does not do the narrator, or us, any good. ‘His car is shit fast he tells me I / couldn’t give a damn.’ He heads quickly back to experimenting, innovating, and we go with him. The second brick in particular sees Finch exploring theories of consciousness, spacetime singularities, gravity and whether or not a clock goes more slowly as it approaches lunchtime. This is not someone who just writes about the view from city bookshops on a rainy day; although there are plenty of those too.

The books have been edited by Andrew Taylor, who (slightly battleworn by what a huge project this clearly was) introduced them at that launch a few weeks back. This was quite an event – a swish hotel, a livestream, proper cameras and everything. Finch was interviewed by Ifor Thomas. In terms of ebullience, anarchy and unpredictability, Thomas is the equal of Finch. They also both share a curious inability to age.

There were a few writers in the room and you could hear the cogs whirring. But where were all the would-be writers? Where were the students? Where, in fact, were the young? I was among the youngest there and, whilst I look terrific for my age, I’m the wrong side of 47. You can learn a lot as a poet from an hour in Peter Finch’s company. Imagining yourself as a piece of furniture. Wondering what inanimate objects would do if they moved. Perspective on being stuck in human form. Writing about big themes without being portentous, overblown or egotistical. Perhaps some think Finch is inaccessible or just not for them. How can I convince otherwise? Well, ‘wet sky like a moved photocopy’ is as near to a single-lined piece of brilliance as I (or rather, Finch) can offer. In those six words we have remarkable compression; an original image; rhythm; sound; and an evocation of sense-memory.

Finch is a Cardiff poet, not a Wales poet. He is urban, and when he explores the rural it is always as a visitor. That is not to diminish the achievement. What poet would want the burden of representing a nation anyway? The poet wants to explore the miniature in the world of the greater; the ignored, the rarely or differently observed. Look at the mess people get into when they become, oh I don’t know, Poet Laureate or something. Finch is specifically and proudly Cardiff, and the ‘Welsh fog’ that some reviewers find themselves (pleasurably) flailing in is PeterFinchCardiff fog.

Anyway, as another critic suggested 15 years ago, Wales is Finch’s adopted land, despite having lived there all his life. His homeland is the international one of Dada, surrealism and collage. You’re going to find poems that will pass you by in these two collections, and you’ll probably even find a few you actively dislike. It doesn’t matter. If you won’t get on a plane because you don’t understand how it works, you’ll never go on an adventure. Plunge in, don’t worry about it too much and let the Finch hop about in front of you, cock its head to one side, pin its beady eye on you and say yes, you might feel a bit challenged when in a sudden flutter I land on your knee – but go with it.

The delight in ripping things up and invention-as-fact gives the energy that powers Finch’s work and reputation. Jimi Hendrix never did wake up lost on the island in the middle of Roath Park Lake by the way, despite what the Western Mail might think – Finch made it up. He is an anarchist in a sharp suit, a punk with the safety pins attaching cultures that are not usually stuck together. Sometimes this leaves the reader confused; why call sequences of poems haikus if they don’t have 17 syllables? And I am not the first to point out that Wales is not bigger than Texas, as one of his most recent poems claims/argues/pretends/derides. But no matter. Long may Finch’s birdcall attract us from the other side of the lake.

Perhaps, as will happen to any poet when they have a huge and impressive body of work to celebrate, Finch risks becoming unfashionable (if he has ever been so, loaded as the word is with connotations of popularity and short-termism). Contemporary poetry has changed so much in the past decade or so, and it would be unfair to judge Finch against it. With the exception of climate change, the themes that concern many poets now – our identities in a multicultural world, social injustice, diversity and equality – are not really touched on. But let’s not criticise a circle for being insufficiently triangular. Finch’s legacy is to create substance from nothing, to defy our knowledge of decay and disappearance with vibrancy, sly humour and indefatigable energy.

Brian Eno once said of the Velvet Underground that only a few thousand people bought their first album, but everyone who did started a band. I hope Peter Finch sells a million of these books, and I guarantee that (almost) anyone will have an urge to start writing poems as they are reading. Try it now. Here’s a one-word poem from Finch. What’s yours?

Rainfall

constant

Mark Blayney, Wales Arts Review - July, 2022

Steven Waling - Litter Magazine

A typical Finch poem is… er no that doesn’t sound quite right… Throughout this collection Finch… no, that doesn’t seem right either… Generally, Finch’s poems are characterised by… Nope. That doesn’t get us anywhere…

Look, the thing about Peter Finch’s poems is that there is no such thing as a typical Finch poem. Well, that’s better, but it really doesn’t cut the mustard either. One stream of Finch’s poetry over the years is the visual poetry, featured largely in the first volume but a continuing interest throughout his writing career. Another is what one might call process poetry, where one sets up a way of generating poetic material and then manipulate it through a deliberate or chance generated technique. Take, for instance, which starts out with a familiar line from an R S Thomas poem: “Just an ordinary man of the bald Welsh hills,” becomes a list of phrases around the theme of hills, then becomes:

sharp grap shop shap

sheep sugar sha

shower shope sheep

shear shoe slap sap

grasp gap gosp gap

guest gap grat gap…and becomes a commentary on the media image of Wales. Somehow, he has gone from rural Wales through sound poetry to cultural comment and personal stories.

The surprising thing about this collection is that despite the strangeness and difficulty of some of the poems, there is a very democratic spirit to the whole kit and caboodle. You might think that a poem which consists of a photocopy blur and daub might be off-putting and impenetrable, but much of the time there’s a real pleasure in them and a connection with a readership (or perhaps a viewership) that is really inviting. The poems from the Writers’ Forum book Dauber, for instance, hint at then idea of haiku without telling you what to think and are visually stunning as well.

Most of these nearly 1000 pages of poetry, however, are not visual poems, and they vary between performance silliness like Modern Romance, based on cut-up Mills & Boons novels:Paula grinned

Pauls pulled

Paula picked

Estelle murmured

Paula enjoyed

Etc…To a personal account of a visit to the urology clinic:

hardly anything hurts here

front of the internet

finding out where it came from:personal history,

recurrent urinary tract infection,

external beam radiation,

infection by parasite,

caffeine, saccharin,

hairdresser, machinist,

printer, painter, trucker,

rubber, chemical, textile,

metal, leather worker,

smoker (greatest risk),

dark tobacco, after that light,

then second hand.

Caucasian,

male over fifty,

worse as you age.

(Urology)From the first poem, in the first volume (a delightful comment on ‘60’s activism), to the final poem of volume 2, a one-word poem dedicated to Edwin Morgan, this collection is a delight. A gallimaufry. A compendium of forms. A dictionary of discovery. A mixtape of marvels. A variorum of voices.

Steven Waling - August, 2022 - Litter Magazine

Poet, psychogeographer, and hero of the Welsh avant garde, Peter Finch is a writer for whom the phrase ‘force of nature’ could have been invented. Come to think of it, he probably invented it himself, or spliced it together in a cut-up. Now in his mid-seventies, the shaven headed septuagenarian feels more culturally relevant than ever, not least because of his verve and iconoclasm. If, like him, you’ve an appetite for literary subversion, you’ll find his double volume Collected Poems good enough to eat.

The books begin at the beginning, so I will too. Like so many emerging poets in the 60s, Finch was inspired by Ginsberg’s “Howl”’, together with The Mersey Sound poets, McGough, Patten, and Henri. Their writing gave him permission to exist outside the literary establishment, and instilled a desire to create his own poetry magazine, the Second Aeon, which launched in 1966. Initially little more than a showcase for his own work, it ran for 21 issues, becoming hugely influential. It brought him into contact with a broad range of writers, including concrete poet Sylvester Houédard, proto-postmodernist Nicholas Zurbrugg, and sound poets like Henri Chopin and Bob Cobbing. Their influence can be seen in Finch’s early works like Antarktika, ‘the visual score for, and transcription from a sound-text composition made on a stereophonic cassette recorder’, and Blats, ‘a collection of none poems’, whose composition involves chance, which, Finch reminds us in his original introduction, ‘is the natural order of things’. Such experimentation is well represented in both volumes of Collected Poems, which are characterised by Seren’s high production values. One of my favourite visual poems from volume one, for instance, is “Walking”, a tribute to the poet Eric Mottram created by photocopying Mottram’s Selected Poems onto a single sheet and then manipulating the text. As Andrew Taylor tells us, ‘Finch then inserts Mottram himself into the new Snowdonia-like textscape as a red dot’. In the original publication, Finch avoided the cost of colour printing by adding the red dots by hand, but Seren has a bigger budget and a broader palette, and Mottram enjoys a more permanent position on the printed page. It’s a striking image that I’ve looked at so many times that my copy now falls open to reveal a red dot ascending a mountain of semi-obliterated text.

Experimentation pervades both volumes, but sits alongside a wealth of accessible material. In one interview Finch says that, when it comes to a poet’s relationship with the public, ‘The trick is to avoid impenetrability and get the balance right’, and I think he manages to do that in much of his writing. While he frequently covers difficult territory, and some of his work is cryptic in the extreme, you can’t help but be struck by the creative intelligence behind it, and the sense that he has our best interests at heart. Bob Cobbing had a word for Finch’s aesthetic – ‘verbivocovisual’ – which is appropriate in that, while you often need to see and/or hear his work in order to fully appreciate it, much can be consumed in the usual way. Indeed, the irreverence and intertextuality of Finch’s visual poems and cut-ups can be seen in his more conventional writing. Take, for example, “All I Need Is Three Plums”, which, as you may guess from the title, is in playful dialogue with William Carlos Williams. It opens:

I have sold your jewellery collection,

which you kept in a box, forgive me.

I am sorry, but it came upon me

and the money was so inviting, so sweet

and so cold.I like the way this exposes the moral implications of Williams’s “This is Just To Say”, forcing us to reflect on the nature of trust, theft, transgression and forgiveness. It transforms the impact of the speaker’s plea to be forgiven, and the language employed to justify his behaviour. It closes:

Please forgive me, I have taken the money

you have been saving in the ceramic pig

and spent it on drink, so sweet and inviting.

This is just to say I am in the pub

where I have purchased the fat guy from

Merthyr's entire collection of scratch and win.

All I need now is three delicious plums.Forgive me, sweetie,

these things just happen.I love the jokey references to the original, like the delightful reworking of the word ‘sweet’ in the final stanza, ‘Forgive me, sweetie’; it exposes the duplicity and latent hostility of Williams’s speaker, inviting us re-examine his professed contrition, reminding us that confessions are narratives designed to excuse the penitent.

Finch’s attitude to the literary canon is gloriously subversive, as can also be seen in his text message reworking of Wordsworth’s ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge’:

‘N Wst Brdg’:

'nvr saw nvr flt clm so deep!!!

rvr flws at hs sweet wll (own):

Deer GD! vry hses seem slp | |

+ all tht BIG HRT lyng still!’Again this is indicative of Finch’s playfulness, which is often overtly comic: if you’ve ever seen him read you’ll know that humour frequently combines with his infectious enthusiasm, making for powerful and often hilarious performances.

As a psychogeographer, Finch’s principal interest is Wales, and particularly his beloved Cardiff. He is the author of Real Cardiff 1, 2, and 3, together with Real Wales, among other place-based books, and hundreds of individual poems about the region. Again his poems about place range from the experimental to the conventional; Wales-themed list poems abound, for instance, such as “The City Region”, which lists Cardiff street names, and “Colon” which presents a list of Welsh battles. I’m particularly fond of his Zen Cymru haikus:

This Wales leaks there isn't one

That doesn't

Is there?We can’t miss the homophonic pun, but there’s more to it than this. To me this poem is quintessentially Finchian, partly because of the humour, and partly because of its unwillingness to be reduced to a single meaning. The implication is that there isn’t a definition of Wales that doesn’t ‘leak’, in the sense that the place will always evade definitive descriptions. Finch persistently works against definition: his writing, just like his favourite subject of Wales, invariably refuses to be pinned down.

In his foreword to the second volume, Ian McMillan relates an anecdote about once inviting Finch to talk to a group of his students. McMillan told Finch that the class needed livening up, which the latter clearly took as a challenge. Having begun by reading a few conventional poems, Finch produced a copy of a Mills and Boon book and began reading from that. As he read he started tearing out the pages and eating them. McMillan considers this ‘a deep examination of the relationship of the writer and the reader, the performer and the audience’, which seems like a fair point. The ultimate meaning of such experiments remains elusive, of course, but the world is better for them. They have driven Finch’s art since the sixties, and while they don’t always find such radical expression as the literal consumption of printed text, they’re rarely predictable, or boring. You might say they’re what make both volumes of Collected Poems good enough to eat, and at close to 1000 pages it’s a copious repast.

Paul McDonald in London Grip - international online cultural magazine - August, 2022

Billy Mills in Ellipitical Movements

Peter Finch’s Collected Poems is a two volume set, with volume 1 covering 1968-1997 and the second 1997-2021. Running to almost 1,000 pages it is, in one sense, a monumental piece of work, as long as you don’t conflate monuments with the past, as Finch is going strong and apparently the first collection for inclusion in volume 3 has already appeared. It is too large a body of work to allow for a detailed reading in the limited scope of a review, so what follows is a number of thoughts provoked by reading these two books.

~

The first thing that strikes the reader is the incredible range of Finch’s work, from ‘conventional’ lyrics through experiments in sound and performance, to visual and concrete work, he is constantly pushing the boundaries of what poetry might mean and of readerly expectations. And he is the master of the formal mash-up, producing list poems in prose that contain elements of found material and sound poetry, or an anecdotal poem that dissolves into its constituent sounds, for example.

This formal range enables Finch to make poems ‘about’ nothing and everything:

Two Interruptions

we should be able to make a

poem out of anything apple

tase shift should we are able

to make a poem (poem) out

of anything shift taste made

a pommel out of it door

should be shift should we

are able to refuse to donate

the poem out of shift anything

shift able to make

Here, as elsewhere, the process of transposition (shift) is made visible, accessible even, to the reader who is invited to inspect the workings of the poem.

None of this should be taken to mean that Finch’s poetry is aesthetic, is art for art’s sake; he is frequently, I might argue usually, politically engaged, and this engagement moves through 1960s radicalism to a disgust at the destruction of his native Wales under Thatcher (“she listened but did not hear”) and a recurring evisceration of arts administrators, corporate business speakers, and bullshitters in general. See, for example, ‘Words Beginning with A from the Government’s Welsh Assembly White Paper’:

a a assembly an assembly assembly assembly and assembly and assembly assembly assembly assembly assembly annexes and arrangements assembly and assembly affairs and authority accountability a achievement assembly autumn assembly a affect an an assembly assembly assembly and a alongside a an assembly assembly assembly allocate assembly and and acts assembly assembly assembly administrative agriculture a an annual and authorities and agency and authorities are accountable address assembly and answerable across assembly assembly assembly assembly assembly and arrangements are assembly assembly are assembly agriculture and and and and arts and annex a assembly approval assembly all after assembly assembly affairs and and assembly assembly and a and account appropriate assembly acts and are acts a assembly are assembly a authority and and able as and a assembly authorities agencies assembly able assembly assembly and a and and a a a assembly assembly and able able assembly about a assembly and a assembly as appointments also and assembly assembly as assembly assembly against as as able and authorities against and assembly are a and a assembly assembly and assembly assembly a affairs assembly authorities and and and and all and ahead and are across and as assembly and assembly a attuned a agency and authority authority and and and and and any agenda assembly a assembly able a a a adopting assembly and and are a authority and afford an ambitious and a an as as an and air and agencies assembly a and administration agency a and assembly agency already an all and and and agencies authority authority as a and and assembling and authority are agency acquired and and address an a a across and assembly and appoint agency a a assembly authorities at and agency and a and an agency assembly assembly agency arrangements and agency authorities a and attracting and and assembly action action action and a and a assembly assembly agenda assembly at all agenda assembly and and appointments also and are also a and a and an authorities agencies and advice advice approximate a assembly and at affairs annual a and assembly and actions assembly assembly assembly and a administering assessment agency assembly assembly assembly a are and agriculture aborigines advisory assembly and adequate appropriate appropriate areas and approximate arrangements are appropriate approximate appropriate arrangements and assembly art assembly are arrangements approximate appricimate appropin approximarly approximin approximit approximate appropinate appropriate approlution approximate apprealin approling approf appross apprit approx approximate appropriate arsembly approt approt apprit aparse amprim arsenit arsenit arsenit arsenit arsenit arsenit arsenit arsenit arsenit approximately assembly and arsen assembly all art and agriculture agenda appropriately alltittle all al aswoon apricot artle at assen ash arsenit assuitable assuage annual after amiddle approximate appealment apparliament arprat aprat art arse alltold approximate flatart anti anemia academic and averted arse art all assembly anti any attitudenal arseweakness all appropriate approximate approximate apripple affected arse affected all affected and any affected apathy apathy and responsibility for ancient monuments arses arses arses and wishing wells

~

Both editor Andrew Taylor and Nerys Williams, who provides the Foreword for the first volume, refer to William Carlos Williams’ idea that a ‘poem is a small (or large) machine made out of words’, which is apt circumstantially as Finch reworks the American poet’s ‘This is just to say’ a number of times but more pertinently because it points towards the central thread of Finch’s poetic; that language is material, and is the material of poetry.

This is as apparent in the ‘plain text’ poems as in the visual work. On one level, it’s the focus on the hard particularity of words in passages like this:

We walk single file. Shellduck on the

mudflats, groyne teeth, breakwater, boat ribs,

wrecked hard-core. the slope to the sea estuary

toughened with a boulder skin rough as a navigator’s

hands.

[from ‘Lambies’]

On another, allowing the levels to be a continuum, the simple beauty of the visual work:

In a number of poems he plays with paradigmatic relationships through the use of brackets, as inn these lines from ‘Fold’:We (us) (I) (you) were (weren’t) (won’t) (will) a (the) (this)

people (pointed sticks) (prime numbers) (purple patch0 taut

(tired) (tiled) (tight as fists) for (from) (frightened) (foaming)

war (wet fish) (wet fist) (wet fear); the (those) (these)

hills (hovering) (hollow) (high) (high) (high) (heated)

(hardened) were (will not) (can not) (can) no

(none) (neither) (normal) harder (holding) (heaving)

(happy as barber’s poles) (hard hosts) (home)

The bracketed items create opportunities for multiple readings, multiple folds through the poem. It is also typical of Finch’s work that they create and seem driven by patterns of sound, and that these have a timeless quality, reaching back perhaps to the earliest poetry in Welsh and English:

the (those) (these)

hills (hovering) (hollow) (high) (high) (high) (heated)

(hardened)

In an amusing but useful note to the poem, we are told: ‘(cant) (explain) (can) (might) (read on)’ (‘cant’ being both a private language and can’t).

~

In the late 1990s, two things happen; Finch begins to play with he haiku and his sense of Welshness, already present as an undercurrent, becomes much more central to the work. And I mean not just his own Welshness, but some kind of exploration of what being Welsh might mean in the late 2oth century, post mining, post-industrial world.

Finch being Finch, there are visual haiku:

sound haiku:nnn nnnn nn nnn n

nn nnn nan n nn nnn nan

nn nnnn n nn non

haiku that nod to the form’s great tradition:

so boundless

frost on the pond

light on fire

and Welsh haiku:

Dim mynediad the farmer’s sign

The cow parsley

Goes right on in

Apparently around this time Finch had learned Welsh but decided to continue writing in English, but to my ears at least it’s an English with an increasingly Welsh inflection:

rydw i am fod blydi i am

rydyn ni rydw i rody i

rodney rodney i am

rhydyn am fod I am I am I am

rydw i yn Pantycelyn Rhydcymerau Pwllheli yes

RS Thomas is an important figure whose presence recurs across Finch’s work, not just as a poet but as a kind of exemplar of varieties of Welshness:

In his work are there traces of this place,

where he was born, reluctant, leaving

as fast as he could? Do the streets of Cardiff echo?

No, they don’t. Do we honour him in this

city as a lost son? Plaque, statue, trail?

No we do not. He wouldn’t want them.

Not Welsh enough, us, for a man redolent of

rural fields and revolutionary fire.

In Wales, cities are alien places.

~

In addition to Thomas, the figures of Williams and Bob Dylan recur. There are a number of reworkings of William’s famous ‘This is just to say’, my personal favourite is this one from 2001 and included in the Unpublished Poems section at the end of the second volume:

Recycled

thj tsayI hv eatentplumat rein thicebox

& wch youreprob savbreakForgive thy

redelicious sosw eet &socold wmcls m

The object made sound.

~

There is so much more that could be said, for example about his use of the list form or the internet poems that work on the page but come to life online. but I’d like to close this review by going back to a Twitter discussion on the nature of experimental poetry started by Beir Bua Press while I was reading these books. What Finch, a determinedly ‘experimental’ poet, shows is is that this kind of work is more formal than so-called formal verse in that it is constantly in search of form, that it delights in failure, or the risk of failure, because it knows that without that risk we are left with the comfortingly numb, it is, in short, whatever you want it to be.

These collected poems are a joy to read; so go read them

Billy Mills in Elliptical Movements, August, 2022

Jon Gower in Nation Cymru - Collected Poems Volume One

Reading this 500 page blockbuster volume of Peter Finch's poetry is like setting off an enormous box of fireworks.

Light blue touch paper, pause, don welder's goggles and then enjoy the pyrotechnics, the magnesium flares of verbs, the sherbet fizz of nouns, the crackling rockets of verse as they variously burst, illuminate and flare.See, it's catching.

And this is only the first volume of his 'Collected Poems,' covering thirty years of busy experiment, poetry making and general rule bending. It's involved some diligent collecting, too as it gathers some material from special limited issues and chapbooks which aren't easily available, thus giving us the opportunity to consider the character, calibre and full range of this restlessly entertaining poet over three decades of writing.

The engine room of verse

His is a singular, special poetic voice and he certainly hasn't stuck to the rules or followed the norms.

Peter Finch was working hard in the engine room of verse during the so-called Poetry Wars of the 1970s - when conservative practitioners battled the avant garde - and has kept on generating verse during a much bigger revolution when online outlets disarmed the cultural gatekeepers and poets found new audiences on the internet.

Throughout all this Finch was his own one-man poetry industry. He notes that he is now 'taking advantage of my modernist upbringing: finding that what I have been doing for thirty years is fashionable again; watching others hijack old ideas and retread them as if they were new and as if they were their own.'

Peter Finch doesn't want words to live calmly on the page, he wants to stand and deliver them and has done so and still does so with great elan and inventiveness.

I've seen him eat a Mills and Boon novel as part of his routine and delight audiences with tongue-twisting, effervescent sound poems which push poetry to the edge and then nudges it over.

'Push the idea on until it breaks, flowers or dissolves,' as he puts it. And because he's done the circuit of readings and literary events he can give sage advice to others who wish to perform their stuff in public.

In "Advice for Perpetrators" he suggests: 'before beginning smile/Before smiling locate the door.'Experimental

The poems sometimes explore Wales and the Welsh landscape through an experimental lens, thus allowing a bit of refraction and contortion. And fun too.

There's a fake biography of R.S.Thomas including two words which can seem to sum up Thomas and his poetry - "Gospel. Austerity."

Finch's is certainly not a po-faced, reverential poetry: he's too delighted in what's there when you rummage around the toy box of language to stand too long in awe of the world or go full Wordsworth.

And he draws on material from many sources to inspire him.

He describes himself as a 'full-time poet, psychogeographer, critic, author, rock fan and literary entrpreneur' and so we get nods to other poets, mappings of places and spaces, sharp opinion, musical references and stories about trying to sell poetry.

The volume includes some of Finch's greatest hits of course, such as "Welsh Wordscape," the first part of which runs as follows:

To live in Wales,

Is to be mumbled at

by re-incarnations of Dylan Thomas

in numerous diverse disguises.

Is to be mown down

by the same words

at least six times a week.

Is to be bored

by Welsh visionaries

with wild hair and grey suits.

Is to be told

of the incredible agony

of an exile

that can be at most

a day's travel away.

And the sheep, the sheep,

the bloody, flea-bitten Welsh sheep,

chased over the same hills

by a thousand poetic phrases

all saying the same things.

To live in Wales

is to love sheep

and to be afraid

of dragons.

It's hard to read this popular poem without concluding that some things never change.

Criticism

The poems arrayed here include prose poems and experimental verse that push individual words about as far as they can stretch: one poem plays with the word "moon" so that it fills a whole bunch of pages.

The poem, "On Criticism," meanwhile, takes the form of various pages from a work of (diplomatically unidentifiable) criticism all scrunched up as if destined for the waste bin.

A poem such as "All I Need is Three Plums" is, in one sense, a long apology, but what a funny one, mixing confession with self-derision and nodding in the direction of William Carlos Williams as it does so (Williams wrote a poem called "This is Just to Say" about purloining some plums and Finch seems to steal the idea as if he's reaching into the same fridge.)

A few sample stanzas captures the abject grovelling of it all:

I have sold your jewellery collection,

which you kept in a box, forgive me.

I am sorry, but it came upon me

and the money was so inviting, so sweet

and so cold.

I have failed to increase my chest measurements

despite bar bells

and my t-shirt is not full of ripples.

I am sweet but that is no consolation.

Your hand is cold.

I did not get the job, your brother did.

He is a bastard I told him, forgive me.

The world is full of wankers, my sweet.

I have lost the dog, I am sorry.

He never liked me, I am hardly inviting.

I took him off the lead in the park and

the swine chased a cat I couldn't

be bothered to run after him.

Forgive me, I will fail less in the

future.

You will see from the above selection of stanzas that one of the hallmarks of Finch's poetry is a sense of fun and it's not often you get to read a poem which is laugh out loud humorous.

The fun can start with poem titles such as "Putting Kingsley Amis in the Microwave" or in opening lines such as 'There are three skinheads in the furniture department/Trying to shoplift a bed' or by fashioning poems in which some of the words are replaced by, say, the word 'Bighead' as in the poem of the same name, resulting in such literary works as 'Taming of the Bighead' and 'How Bigheaded Was My Valley.' Not that Finch is a bighead, far from it.

Product placement

Finch can find material pretty much anywhere. He fashions one piece from headlines found in monthly newspapers published for ex-pats and people of Welsh descent in the U.S.A.

He formulates a sound poem to replicate the mechanical noises of a Grip-vac, which I imagine is a sort of vacuum machine.

There is other shameless product placement too, such as 'The Perfect St David's Day Gift' namely some foaming 'Felinfoel Welsh valley Shampoo/made from real Welsh coconuts.'

Music

It's always busy stuff on the page as in the mind. He creates an A-Z of place names around the Severn estuary. He name checks a host of poets, from John Tripp through R.S.Thomas and Thom Gunn to J. H. Prynne and to his buddy in poetic exploration, Bob Cobbing.

He references plenty of music and musicians along the way, from blues to jazz, from Philip Glass to Chubby Checker, the Shirelles to Lou Reed, George Harrison to John Cooper Clarke. After all, all art aspires the condition of music.

Restlessly, questioningly, adventurously Finch cuts up text and mangles syntax. He finds the stuff of poetry whilst perusing the material on an O.S map of the Brecon Beacons or in examining the components of the overlooked landscape of the Wentloog Levels.

He does all this with both brio and bravura because Peter Finch is a swashbuckling buccaneer in Welsh poetry who does nothing less than take language for a ride. A rollercoaster ride.

His joy in doing all this is positively contagious. Celebrating the pulse, rhyme and rhythm. Chancing it. Pushing language into all shapes. Testing, testing, testing it until the line finally breaks.Jon Gower in Nation.Cymru, 17 September, 2022

Jon Gower in Nation Cymru - Collected Poems Volume Two

In the introduction to this second doorstop-sized selection of work, the poet Ian MacMillan suggests that 'If and when the great poet and performer Peter Finch reads this intro he'll stand up and sing it in a falsetto voice which will be all the more startling and liberating because he'll be on a mid-afternoon bus in Cardiff. He'll then sing it backwards and then he'll just sing the vowels and then he'll just sing the consonants. He'll encourage his fellow passengers to join in and many of them will although some will get off before their usual stop.'

Macmillan goes on to imagine his fellow poet cutting up the pages of his own book and rearranging the strips to make a new sense which he dubs Finchsense. You get from this a real sense of the energy, gusto and restless sense of invention which are typical of Peter Finch, both as poet and performer, as editor and literary entrepreneur.

Indeed such is the energy of the man that Ian Macmillan suggests that there is more than one Peter Finch and that all these Peters are working to create many different kinds of poetry at the same time.

Humour

Those poems invariably have plenty of verbal crackle, snap and pop, exuding a sense of fun and adventure. But in this second volume there are more personal poems which map out some of the poet's life. A poem called "Urology" evokes a visit to a hospital department and yet manages to keep the Finchian/Finchist/Finchesque humour very much alive as these sample stanzas demonstrate:

On the screen it's like miniature DynoRod

hunting my house drains

water running so it slides

headlamp camera scouring plunger

At twenty meters they found a ring-seal loose

have to dig that out.

On the notes when I browse them

while the nurse is out

the sketch looks like a sea anemone

still life: bladder with flower

done in biro

sideways on the urine analysis

Red cells present: too

many to number.Finch can find the stuff of poetry pretty much anywhere. He doesn't need to scale mountains or wait for visitations by the divine. One poem concerns a cancelled trip with Winston Rees Travel. There's a poem made up from "Words Beginning With A From The Government's Welsh Assembly White Paper." There's a lot of stuff about Wales as you can see in quirky titles such as "Llywarch Hen SMS with Fault," "Ysbwriel," Rhai Caneuon Cymraeg" and "Mid Period Anglo Welsh Endings." In "The Student House" he just calls round to his son's abode and finds a poem among the disorder:

We arrive through thin snow to

my son's student house where

no one has been for three weeks.

The ice has turned the air to knives.

I find a ketchup-smeared plate

frozen at 45 in the unemptied

kitchen sink. A river of lager

cans flows down the hall.

As I stamp into the lounge

keeping my feet alive the ghosts

of dust come up around me like

children. The stains across the

sofa look like someone has died.

Meanwhile a visit to a house in "Ty Draw" road in Roath in Cardiff, where the poet had previously lived, brings with it a different sort of disappointment:

Round the back where the past might

still congeal among the rust and residue

they've renewed almost everything.

I once painted my name on

the lane tarmac in front door green

but the rains have long washed it. In a life

how much do you have to do to outlive it?

They kept chickens next door and I

loved them but today no sound

remains.

A door opens and a face asks me

what I'm doing here where housebreakers

would walk. I say chasing the

past. I used to live here. Do you remember me?

He shakes his head.

But at the top of the hill there's

smoke from the train, still rising,

as it trucks its coal to the dockland sea.

I can see it, smell it, hear its gouts of grey

and black. Smuts. Steam. On and back.

I've written it now.

And you've read it. So, something remains.

In a smashing poem which follows the poet's odyssey into language and effect called "Shock of the New" Finch asks 'How have we got so far/On foot? Long hills full of light, /towers of distrust, /the music of falling trees…'and explains how 'when we/began it was a matter/of dealing with demons…'and goes on to detail the tasks a poet faced, such as understanding the land or the human condition and the challenges faced when 'Our educated peers outran us.'

Enormous zest

The poem ends by pondering 'Does much matter/when it all ends.' This fine collection doesn't answer that question perhaps but shows us with enormous zest and energy how much it does matter -as we go through life - to be alert to it all, to the joyous, raucous possibility of language, of paying sharp attention to what's around us and inside us.

Peter Finch enjoys revelling in verbs and making nouns fidget, cutting up texts and even making brackets interesting. The two, huge volumes of his Collected Poems show how he helped transform the poetic landscape of Wales, set up crazy skyscrapers among the booths, how he shook it all up.Jon Gower in Nation.Cymru 19th September, 2022

Air Freshners for the Soul

Rupert Loydell's poem "produced by writing through both volumes of Peter Finch’s Collected Poems (Seren, 2022), using the first and last lines of each page, but selecting from them" Included in an edition of Andrew Taylor's online magazine, M58. Read here.

click

here to add the

Peter Finch

Archive

to your favorites