Coming up Randolph Avenue I can feel my arms pulling from their sockets.

It's hot. There is sweat on my forehead. The Avenue seems so enormously

long. I'm taking my second aeon pages, printed in Cardiff, carried

on the 125 to Paddington, hauled through the Underground and now lugged

from the Maida Vale Tube to number 262, up the steps, through the

door, along the hall and then down into Bob's vast basement. 1500

sheets on yellow paper. My pages for ALP's annual catalogue, Bob's

co-operative answer to the unsolvable small press distribution problem.

It's the early seventies. He makes me sweet tea to aid recovery. We

sit amid the paper stacks, floor to ceiling packages, boxes of Gestetner

smears, unbound editions of Lee Harwood, Allen Ginsberg, Allen Fisher,

Micheline Wandor, Jiri Valloch, Neil Mills, Criton Tomazos, off-prints,

boxes of staples, cartons of ink, a z-bed, a broken tray, half a tea

maker, a crushed yin-yang cube. The phone goes and it's some contributor

to And, Bob's legendary magazine. At this time I've never seen

And, published as loose sheets in a plastic bag and distributed

among those who happen to be near when it actually appears. "Ah,

yes", says Bob, using that deep resonating voice of his, before

treating the caller to a fluid rejection of whatever has been sent.

Bob blames time, mail, quantity, printing difficulties, and his co-editor

John Rowan for not liking the stuff before swiftly hanging up. Ever

interested in the ways of publishers and editors I ask, "Does

John see all this material?" But Bob's gone upstairs again to

make another hot drink.

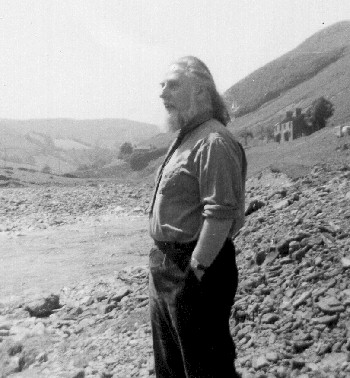

Bob Cobbing at

Cwmystwyth - 1973

We're at Cwmystwyth on the back road through the Elan Valley heading

for a reading organised by Mary Lloyd Jones at Aberaeron. I'm driving

a Hillman Avenger which is supposed to be a hot hatch but actually

overheats at the first opportunity and usually breaks down if you

drive it at over 40. Bob's never been to this part of Wales before.

The green desert. We stop at an abandoned lead mine where a vast slurry

of spoil sprawls down the hillside. The village is deserted, none

of the cottages have roofs and the machine used for pulling the ore

from the soil is either wrecked or gone. The wreckage is weathered.

Vegetation is beginning to grow back. I take a b&w out of focus

photo on my tiny instamatic, find a bolt from some ancient tram sleeper,

and a rock with a mark on it that could be a word. We clamber over

the sliding piles. Bob roars juka kuru roku juka kuru roku joku kuro

roko joko kuru roko, his Kerouac tribute, which echoes back at us

off the sky. Cymru. Poetry. Land of Bards. Jack Kerouac. French Canadian.

Breton. Almost Welsh. Of course.

In the back room at my house Bob sits before my BBC-B computer. It's

the early 80s and he's in Cardiff for a reading at the Oriel Bookshop.

I've programmed this weak-brained but so-simple machine to assemble

words from a common wordpool and make them into random sentences.

The poem streams up the screen like a demented Jackson Mac Low. There's

no printer attached, no storage device for the computer's output.

It creates into electronic space and then disappears into the void.

Bob is fascinated. "It plays little poetry films, doesn't it?

Can we get this to rearrange the letters that make up the name Edwin

Morgan?" We can. It's simple enough, written in BBC Basic the

new program takes about fifteen minutes. Bob is working on a poem

to celebrate the great Scots concretist. I save it onto cassette and

then load. The BBC-B begins to rearrange the letters of Edwin Morgan's

name at high speed: WNIDE GARNOM NAGNIRWDE OM DWRG ENIMONA. Bob sits

seemingly stunned and then begins to catch lines he likes and to scratch

them onto a pad he's pulled for his jacket pocket. The screen is a

blur of white. The endless permutational stream rolls towards infinity.

The poem is in Bob's collected works, somewhere. Edwin Morgan approved.

On the train back from Sunderland Bob has bought a whole crate of

Newcastle Amber Ale and sits with it between his legs. He's sockless

in sandals. I've never seen him any other way. We've been on the Cobbing/Finch/Rain-in-the-Face

northern tour playing in dark rooms above pubs and poorly attended

halls in Newcastle and in Whitley Bay. These are the places where

you worry if your jacket falls to the floor because it will be too

filthy to put on again when you pick it up. Rain In The Face, a duo

made up of Paul Burwell and David Toop, use guitars with errant tunings

and dementedly random percussion. Burwell is a master of new and rediscovered

musical instruments including the amazing wasp phone with its insect

driven membrane. The band use things you bang and things you hit.

Bob has flailed and roared through the set pulling the disparate elements

around him into one forward flowing drone. The evenings have been

brilliant creative successes even if the audiences have been small.

The train ride is long. I try to talk Rain In The Face into using

a piece of traditional rock and roll, unexpectedly, right in the middle

of their set. "Imagine the faces of the seriousos if you suddenly

broke into Whole Lot of Shakin." They smile and say they'll think

about it, but they don't, (although David Toop was heard later performing

a sort of slow falsetto rock song among his otherwise progressively

random set). Bob tells us that he once tried to use Chuck Berry lyrics

in one of his performances but they came out sounding like standard

Cobbing. Of course.

In Oxford in the nineties Bob and I are reading to the usual audience

mix of fans of the avant garde, small press publishers, literateurs,

fakes, academics and random passers-by. Bob's set uses no text whatsoever.

I've not seen him read for a few years and am amazed by the transformation.

There was a time when everything Bob did was connected with text of

some sort. Writers Forum publishing and his own performances were

indivisible. Now here was the great man, teeth less in number but

stature undiminished, rolling through an hour-long reading of standard

Cobbing greatest hits without a single piece of paper visible anywhere.

The poems - Are Your Children safe In the Sea¸ Tan Tandinanan,

Alphabet of Fishes, Soma Haoma, Kurrirrurriri mostly come from

the early period. They are as they were but they are changed. They

are extended, bent, turned, increased. Cobbing is now Bob Dylan, using

the old songs but changing the tunes. Retreading, remaking. The past

recycled but with all the power still in place. The audience, some

of whom have never encountered Cobbing before, love it. There is cheering.

People hang onto every roar. Towards the end, as if for a moment lost

for inspiration or forgetting the next item on the set list, Bob turns

towards a cheap print of the local landscape. It's framed on the wall

behind him. His eyes brighten. Back to his audience he stares straight

at it, his head no more than a foot away. "raar rop rill room

rut up up rut roop roop roop" His voice soars. The landscape

becomes poem. Cobbing's voice booms up to fill completely the excited

room. He's in his seventies and has been on his feet for at least

sixty minutes. He can't see to read properly, in this light, with

these glasses. Why slavishly follow the texts he's been using for

decades? Who needs them. Great applause breaks out around me. Bob's

finished. Best I've heard him in thirty years.

I guess the most important thing that Bob taught me was that the

voice could learn from the machine. Once you've heard voice treated

on tape, he explained, then you can make that sound yourself. He'd

play me a tape of voice slowed and then make the same deep rolling

sounds. Then we'd try it with a tape speeded up and with, maybe, the

middle section cut out and spliced back in upside down. The taped

sound would flicker and zip. Do it, he'd say. And we would. We don't

need machines to make work. They can show us new ways but once those

have been experienced then we are on our own.

Bob was the great centre of the left hand for the forty years between

1960 and 2000. Mention avant garde, alternative, innovative, concrete,

sound, textural, sonic, visual, experimental and Bob would have a

part in it. Official recognition didn't matter. He relished the bad

reviews he'd got and used them as part of his own self-promotion.

What was important was that the door be open and that the work carry

on. His creativity in both sound and vision was intimately linked

with small publishing. Big stuff, hard covers, and fine print were

all well and good but most of the time just not flexible enough or

fast enough for his needs. Bob would make a piece in a morning - a

smear from the back of a Gestetner stencil cut-up and rearranged -

and in the afternoon he'd publish it. Writers Forum, his curiously

old-fashioned sounding imprint, brought out more than a 1000 items

during his lifetime. The editions were small. But they were significant.

We're sitting the White House, the hotel bar next to the Poetry Society

in Earl's Court Square. Criton Tomazos is standing on the mantle piece

ripping bits out of a book and chanting. Bob has drunk almost half

a bottle of whiskey and is still standing, or leaning, at least. Jennifer

arrives in her small car to take us home. The vehicle is full of boxes,

papers and bits of equipment. We push Bob into the front seat but

there's no room for me in the back. I climb onto the roof rack. We

drive. Somehow we get back.

Are you a concrete poet or a sound poet, I once asked Bob. By concrete

I guess I meant visual. Bob's answer was immediate. There's no difference.

He showed me. Anything can be read he insisted. He took a set of visuals

from the book we were working on, Songsignals, and began to

roar them out. Impassioned, accurate, active, elemental, real. They

are the same thing, sound and vision. In Cobbing's hands they are.

Bob Cobbing - Such a life.

Peter

Finch

Bob

was buried under the trees at the City of London Cemetery, Manor Park

on 11th October, 2002

For more

tributes visit Bill Griffiths' small press pages at Lollipop

(no longer there

when I check in 2023 - a resource lost)

Damage

for bob cobbing

antimacassar cryptography

corporate Cirencester

corpuscular christigineous igneous conflation

creel cruel scrim cylindrical cricoid

crankshaft creosote crimson coronet

cormorant carboniferous cynical cystitis

Cadogan

canton

capper cyncoed piepowder

criddle cree crip ip

oop

oodle

iddle cron

crarp crap

croonmeanfester

middle piefancier

dally rinkle stammen

damaged cantonment kings road rusted

deal dominion antique meal voucher

real attack rich managed aromament rings

sandwiched busted dole linoleum frantic

mile pouch racked itch sings minion

advantaged canton crapper pie-eyed

kingdom doodle

fun irreligious

ethic ah yes

excited slight sweat

smile breath

mighty right sweet breath death

frightened tightener

fun was yellow flower is

drown word

word road eastender

extender

Peter

Finch

back

to the top

back

to the Peter Finch Archive